Home

About POP

Home

About POP

Browse by:

Statistics References

Cheap Literature, 1837-1860

Notes on Penny Bloods

POP is first and foremost a bibliographic reference. I offer the following literary history simply as guidelines until I have attained a comprehensive understanding of penny bloods as a whole in my dissertation.

Penny bloods

Adaptations -

American reprints -

Translations from the French -

"Original" works

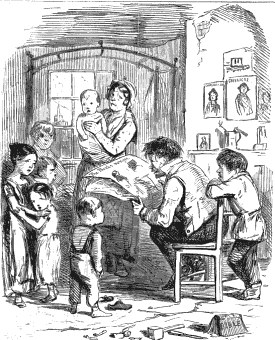

Penny bloods are novels published either in penny periodicals of varying sizes or in weekly autonomous penny numbers, usually comprising eight pages with a woodcut on the first. Serials from periodicals could also be reprinted in stand-alone editions. Both forms of seriality, easing the financial burden for both producers and consumers, date back to the eighteenth century.

The penny bloods' novelty laid in their cheapness. Number-books like Pierce Egan the Elder's Life in London (1821-1824) were lavishly illustrated and sold in shilling monthly parts, as were Charles Dickens's serial novels. Penny periodicals, the first of which appeared in 1828, were mainly concerned with politics and/or humour until bloods came along. Penny bloods were therefore the first to offer novels in penny numbers at a time when a triple decker cost 31s 6d and circulating libraries charged two guineas (42s.) for a yearly subscription.

Precursors: Compilations

Penny publications dedicated to crime and violence started with the Calendar of Horrors (April 1835-Dec. 1836), published by George Drake and edited by future prolific blood writer Thomas Peckett Prest. The latter was a man of the theatre when he started editing compilations for Drake, among which the Magazine of curiosity and wonder (Nov. 1835-May 1836), The Singer’s penny magazine (1835-1836), and The Penny Play-Book (1836).

Prest was then recruited by Edward Lloyd for what became a long-lasting and remarkably successful collaboration. He produced three compilations (History of the Pirates of All Nations, Lives of the Most Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads, &c., &c., and The Gem of Romance) before starting to plagiarize Dickens.

Penny bloods

Adaptations

Penny bloods took off with Penny Pickwick (1836-1838), Prest's plagiarism of Dickens's Pickwick Papers (1836-1837). All of Dickens's works up to and including American Notes for General Circulation (1842) were plagiarized, and not just by Prest. There was for instance at first competition over the adaptation of Oliver Twist (1837-1839) between publishers Lloyd and James Pattie.

Fiction was not the only source for adaptation: the theatre was another. Prest summarized popular dramas for Drake in The Penny Play-Book (1836), for Lloyd in Tales of the Drama (1837-1838) and in the "Dramatic Tales" department of the Penny Sunday Times (started in 1840). He then moved into full blown adaptation with Black-Eyed Susan (1838), turning Douglas William Jerrold's celebrated comic three-act play into a 610-page novel.

The other industrial-scale author of penny bloods, James Malcolm Rymer, also took the stage to the page with Don Caesar de Bazan (1845), inspired by a play of the same name, itself taking its protagonist from Victor Hugo's Ruy Blas (1838).

American reprints

Early on, the Novel Newspaper (1839-1846) took advantage of the lack of Anglo-American copyright to reprint recent American literature (and out of copyright English novels), initially raiding James Fenimore Cooper's production, making him the most reprinted author in penny bloods.

Whilst the Novel Newspaper took its copy texts from middle-class publications, Lloyd and George Purkess turned to the cheap literature of Boston, burgeoning in the second half of the 1840s, when looking for reprints. They were the first publishers (and nearly the only) to bring authors like Maturin Murray Ballou and Osgood Bradbury to the English public. Only Joseph Holt Ingraham was reprinted by both Lloyd/Purkess and the Novel Newspaper.

Translations from the French

French theatre had a great influence on English theatre, which in turn fed the penny bloods. Following Eugène Sue's success with Les Mystères de Paris (1842-1843), the French romans-feuilletons also became an important source for penny bloods. The works of the now greatly revered Alexandre Dumas, author most famously of Les Trois Mousquetaires (1844) and Monte Cristo (1844-1845), often first appeared in English in penny format.

The Novel Newspaper reprinted American translations from the French. New translations were to be found mostly in the periodicals Family Herald, London Journal, and London Pioneer, or published in numbers by George Peirce and William Dugdale.

The Anglo-French Copyright Treaty of 1851 limited the goldrush to a decade by imposing financial barriers which penny publishers purposefully avoided to keep their wares cheap.

"Original" works

Penny bloods which were not adapted, reprinted, or translated from other sources were nevertheless inspired by the others. They typically ran between 15 and 52 numbers, yet very successful titles went on for more than a year: Gentleman Jack ran 205 numbers, nearly four years. A small number, no more than twenty, also made it onto the East London stages, sometimes even before serialization had been completed.

Some of the most famous penny bloods, written in the late 1840s, inscribe themselves clearly in the Gothic tradition, such as Rymer's Varney the vampyre and Reynolds's Wagner the wehr-wolf. Highwaymen novels recur throughout the period, written by Henry Downes Miles, Prest (The Old House of West Street), Rymer (Claude Duval), and James Lindridge (The Life and Adventures of Jack Rann).

Following in the wake of Sir Walter Scott, Scottish and historical themes abound. Pierce Egan the younger, responsible for reviving the Robin Hood myth, wrote numerous historical romances often set in medieval times. The successes of Frederick Marryat and Cooper were imitated (Gallant Tom!, The Death Ship), but the fade for nautical novels was dying out.

Penny bloods also dwelt in the world of domestic romance, with its cottages and daughters. Hannah Maria Jones had been an immensely popular author going into the 1830s: her Emily Moreland (1829) sold 20,000 copies. Penny publishers variously plagiarized, reprinted, and published her works. Rymer also adopted daughters as his subject, as in Jane Brightwell; or, the farmer's daughter and Grace Rivers; or, the merchant's daughter.

Sue's Mystères led not only to translation but also to imitation and appropriation. George William MacArthur Reynolds's stunningly popular The Mysteries of London showcase a similar socialist sentiment. It should be noted, however, that the interest for slums and slang are not a French import: it can be traced back to Pierce Egan the Elder's Life in London, mentioned above. The metropolis' poorer East-end neighbourhoods remain the locus of penny titles like The Blind Beggar of Bethnal-Green and Pretty Bessy.

True crime, until then the subject matter of broadsides, inspired works such as Alexander Somerville's Eliza Grimwood, written in direct response to a murder whose victim bore that name.1 News turned into fiction foreshadows naturalism's heavy reliance on newspapers for inspiration and documentation.

Unsurprisingly, bloods, written in the metropolis for a vastly urban audience, bring forth the urban Gothic that will dominate its fin-de-siècle revival. The only creation to have survived to this day blends urban mystery with decisively Gothic horror: Rymer's Sweeney Todd (originally "The String of Pearls").

Successors: Penny dreadfuls

From 1860 onwards, though the bibliographical format of penny bloods endured, they were replaced by penny dreadfuls. The product of new authors (e.g. Samuel Bracebridge Heming, William Stephens Hayward) and new publishers (e.g. Edwin J. Brett, the Hogarth House), these serials targeted a younger audience. Non-serial cheap formats, such as the single-volume novel and the yellowback, also appeared.

Given the specialization of markets and the consequent diversification of forms, which would complicate largely the bibliographic definition of "cheap literature", POP will not extend beyond 1860.

Glossary

- Drop-head title

- Title on the cover of the first number of a stand-alone serial or repeated at each instalment in a periodical. Also known as caption.

- Gutter

- Spine of gatherings, where is vertically printed the publisher's imprint, and sometimes the price and/or advertisements for other works.

- Re-issue

- Same edition, but different title-page.

- Wrapper

- Coloured paper cover of monthly parts, often illustrated.

1 To learn more about the Eliza Grimwood case, read John Adcock's compelling account in his post "Who Murdered Eliza Grimwood?" on his blog Yesterday's Papers.

How to Cite

Léger-St-Jean, Marie. Price One Penny: A Database of Cheap Literature, 1837-1860, priceonepenny.info. Last updated 29 December 2021. Accessed 26 July 2024.

© 2010-2021 Marie Léger-St-Jean

© 2010-2021 Marie Léger-St-Jean

Contact: marie.leger.st.jean_at_gmail_dot_com

Last Updated: 29 December 2021